xunxar

xunxar  xunxar Follow transfemarmand asked: yay, you finally read iwtv! I’ve been D Y I N G to hear your take on Armand’s whole deal basically since I received my ARC

xunxar Follow transfemarmand asked: yay, you finally read iwtv! I’ve been D Y I N G to hear your take on Armand’s whole deal basically since I received my ARC xunxar answered: I know, I know. It took me approximately one million years and at least five different people badgering me before I got around to reading it (in my defense, I’m not really a fantasy person), and then this ask languished in my inbox for almost three months. I would apologize for that part, but, look, I needed that time to slowly lose my mind. And go to Venice for research. Did I mention losing my mind? Because that happened.

xunxar answered: I know, I know. It took me approximately one million years and at least five different people badgering me before I got around to reading it (in my defense, I’m not really a fantasy person), and then this ask languished in my inbox for almost three months. I would apologize for that part, but, look, I needed that time to slowly lose my mind. And go to Venice for research. Did I mention losing my mind? Because that happened.

Anyway, here I am, finally circling back around to give you my take on Armand’s Whole Deal. You’re welcome. I hate you, by the way. I should make you reimburse my travel expenses.

ETA: This post breached containment! For those of you who are new here - hi, I’m Noor or xunxar, and when I’m not being fannish, I’m a postdoc at the CEU Department of Historical Studies in Vienna. In 2025 I was a visiting scholar at the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, where I worked on the first draft of my upcoming book, May Your Face Turn Black: Religion and the Racialization of Slavery, 200–1300 CE. All my posts about/analysis of Interview with the Vampire (which you can find tagged #fandom: in delusions of increasing grandeur) assume that it’s a very thoroughly researched work of speculative metafiction drawing inspiration from historical events and figures. I do not think Daniel Molloy is or has interviewed a real vampire, but sometimes I’ll link to/reference a truther’s post if they make interesting arguments or have unique sources.

Back to your regularly scheduled programming.

Armand is a really interesting character in Molloy’s alleged memoir because he alone is presented nearly without apology. Louis de Pointe du Lac, Claudia de Pointe du Lac, Lestat de Lioncourt, and most minor characters appearing in New Orleans, Romania, and Paris are accompanied by painstaking and extensive documentation: say what you will about the truthfulness of the narrative Molloy weaves, there really was a British journalist named Morgan Ward whose critically wounded Romanian lover was shot point-blank by Soviet soldiers on December 17, 1944, and a Col. Jonah Macon of the 92nd Infantry Division really grew up down the street from the Pointe du Lacs, and died a bachelor at that. By contrast, Armand—our protagonist’s lover of 77 years and arguably the novel’s main antagonist—is presented to us with a single blurry photograph of unknown provenance and an actively hostile narrator.

The vampire Armand was either born or turned into a vampire in 1508, if you’re inclined to believe him. He was allegedly sold into slavery as a child by his parents under the guise of sending him to work on a merchant ship (on another occasion, he told me his first memory was running from slavers in Delhi), and at fifteen was bought by the Italian painter Marius de Romanus. “Rescued,” he cut in waspishly when Louis told me this.

Louis, whose hand was resting on Armand’s thigh, patted him twice and offered me a smile. It felt like being let in on a joke. “All right. Arun here was rescued from a brothel by his maker. Marius called him Amadeo. It was Amadeo in the painting.”

The painting Louis was talking about was Palma Vecchio’s Adoration of the Shepherds with a Donor, which Armand showed him one night in late 1946 when they broke into the Louvre on a date. Allegedly, it depicts a twenty year old, still-human Armand who’d been loaned out to Vecchio by his maker to use however he liked—“Amadeo had a skill,” said Armand in a blank-faced protest that came off as pathetic by design—but the resemblance pretty much ends at the dark, curly hair, and no matter how you slice it, a painting from between 1520 and 1525 couldn’t depict a twenty year old Armand, or Amadeo, or whoever. Seven years later, dying of some unspecified illness, Amadeo was turned. By 1556, his maker was dead and he, newly minted Armand, was leader of the Paris coven, which was apparently a Satanic cult before it was an avant-garde theater troupe. Despite—again, allegedly—never wanting the job, he held onto it for just shy of 390 years, and refused to give it up when Louis suggested as much.

It’s an odd choice. Molloy goes out of his way to establish the veracity (or at least the feasibility) of the rest of his tale, even where the details are so minor we would forgive their omission—see above—and especially when the subject of the interview obfuscates. Molloy provides the obituary of little Benjamin Paul Frenier, printed in the Southwestern Christian Advocate, and a photograph of his headstone: November 4, 1916–January 19, 1917; in chapter seven, the fictionalized Daniel Molloy who serves as our narrator (and whom I’ll call ‘Daniel’ from here on out to better differentiate character from author) bemoans the fact Louis doesn’t remember the exact day in August of that year that he took Jonah Macon out to the bayou, or else he’d have gone looking for weather reports. Where Armand is concerned, however, we’re informed he’s an unreliable narrator and Daniel doesn’t place much (if any) stock in his story, and…that’s it.

There are a few possible reasons why you might do this. Sequel bait is an obvious one: introduce a character with a long and complex history, explore almost none of it, and you’ll drum up interest in a follow-up. Hell, maybe as we speak Daniel Molloy is on a research binge about the Lodi Dynasty! Sign me up for the preorder, honestly.

Another reason may be to strengthen the novel’s core themes. @omegadanielmolloy has a really interesting meta essay here on reading Armand as a personification of time, particularly of aging/growing old. He is ancient and manipulates memories; he is nearly all-powerful, yet consistently passive. Claudia, eternally young, is perceived by him as a threat, while he’s a threat to Daniel, who spends much of the novel grappling with his memory loss and terminal illness. In this reading, Armand is represented in the documentary evidence as a blurry photograph and nothing more because he isn’t meant to represent any particular historical figure(s), but rather everything that fades with time.

This brings us to door number three: another obvious possible reason for a lack of documentary evidence is that, well, maybe there isn’t any. You can’t prove a negative, and the further back in time you go, the harder it will be to find any records. Armand is allegedly more than 500 years old, and given he can survive in sunlight, we can probably take that to be true in-universe (how old does a vampire need to be before they can do that?)—between time and Armand’s dishonesty, it’d be perfectly reasonable to assume there’s simply nothing left to either support or call into question the veracity of anything predating the Théâtre des Vampires.

Except… Amadeo, favorite muse of High Renaissance painter Marius de Romanus, provably existed.

Marius de Romanus (fl. 1481–1535) is a somewhat obscure name these days, but he was well known to his contemporaries, if not always well regarded. Of his early life, very little is known, but he lived for many years in Samarqand, present-day Uzbekistan, which was at that time a major population center of Iran-u-Turan and the beating heart of the Timurid Renaissance—an artistic movement as influential in the Islamic world as the Italian Renaissance was in the Christian world—before settling in Venice in 1498. From the Venetian State Archives (ASVe), collection ST13:63R:

Date of the grant [of citizenship]: 1523-04-20

Latin name: MARIUS DE ROMANIS

Italian name: MARIO DI ROMANIS

Titles of the privileged [person]: CIRCUMSPECTUS VIR PRUDENS VIR

Type of [citizenship] grant: PER PRIVILEGIUM

Type of privilege: EXTRA

Origin: SANMARKAN

Geographic area of origin: SAMARGANTE

Privileged [persons] in the document: 1

Date of the reference law: 1305-09-04

Place of residence at the time of the grant: VENEZIA

He has been subjected to probation and verification of the requirements.

Limitations of the privilege: PROHIBITED FROM NEGOTIATING WITH THE FONDACO DEI TEDESCHI

Years of residence in Venice: 25

In his home in Samarqand, de Romanus entertained a number of Venetian merchants and artists over the years. Venice held close ties to the Islamic world in the 15th century, and while most were content to travel no further than Egypt, where Venetian merchants would exchange Balkan slaves for Persian carpets, some more adventurous or enterprising individuals went on to Samarqand or Cambay, spurred on by the popular travelogues of the time and the promise of one-of-a-kind souvenirs to bring home to the Serenìssima. De Romanus—whose name as we write it today (with the ‘u’) is nonsense, but as he did, de Romanis, means “of the Christians”—was a friendly face in a strange land.

Once relocated, de Romanus quickly found his footing in the Venetian school, and was particularly influential in what we now call the Venetian Oriental mode. This movement differs from its inheritor, l’Orientalisme, in that it attempted to accurately reflect the aesthetics of the Mamluk and Persian worlds. In many ways, Venice was a bridge between East and West, and its artists sought to “show their work” (though this dedication to accuracy did not extend—despite relatively high rates of Arabic literacy in the merchant class—to the pseudo-Kufic calligraphy commonly seen on the hems of painted gowns). If the veristic ideals of the Oriental mode strike you as rather… classically Roman, you are not alone. Semi-ironic Interview truther and exceptional classical art scholar thenecessarypart posted some musings on classical influences on the Oriental mode and what we might be able to infer about Marius de Romanus’ origins on dreamwidth, and it’s definitely worth a look. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if some of xir insights turn out to be predictive.

In any case, de Romanus, who had lived for many years in the East while his contemporaries were reliant on only brief holidays or often artifacts alone, was regularly consulted for his expertise, and was commissioned for several works of both secular and Christian religious theme. His style was at the time highly controversial, being almost a photorealist centuries before photography. The original The Temptation of Amadeo (1498–1522), a masterwork of the Oriental mode, is said to have included a pair of paintbrushes on the ground for no reason other than that one of de Romanus’ apprentices had left them there, along with fallen leaves and the mending on the model’s hose. Unfortunately, this painting was lost in the 1860s, and the copies—painted by some of de Romanus’ apprentices—are significantly less realistic in their execution.

Among his surviving works, Slave Boy with Severed Head (1533) is perhaps the most well known. It’s currently housed in the National Gallery in London. A reader of the Interview will also recognize his Christ Beset By Legion (1535), a reproduction of which can be seen staged in the photographs of Louis de Pointe du Lac’s Dubai penthouse in the insert. The original—and I’m sure this won’t shock you to hear—is in fact in a private collection in Dubai, but I’m pretty confident Molloy’s photographs aren’t of the owners’s home. I don’t know about you, but if I owned one of the most famous stolen artworks of all time, I would not let a Pulitzer-winning investigative reporter take a look around my house, and if I were a Pulitzer-winning investigative reporter and found out where Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee was, I would not spend two paragraphs on it and then go back to claiming the owner was a vampire. I would be cashing a ten million dollar check and then writing a book about the Gardner heist.

(Someone please write or rec me a fic about vampires doing the Gardner heist.)

Christ Beset By Legion is one of Marius de Romanus’ final works, and in it we see a higher degree of stylization than his earlier paintings, though not a total departure from his earlier verism. The look of pain on Christ’s face is nearly grotesque. This realism of expression and the high contrast composition went on to greatly influence Caravaggio, whose Narcissus (1597–1599) was—prior to Longhi’s very convincing argument in 1916—thought by some to be a de Romanus. Many art scholars still believe it is a master study of a lost original, the model for Narcissus none other than de Romanus’ beloved Amadeo.

Detail of Narcissus.

Another famous painting whose model has been suggested by some to be Amadeo? Botticelli’s Judith Leaving the Tent of Holofernes (1497–1500). Molloy certainly seems aware of the connection:

Louis’ personal assistant was a tall, sweet-faced twenty-something with a head of unruly curls that belonged in a Botticelli painting. He introduced himself as Rashid, no last name, worshiped Louis as a god (his words), and dressed in head-to-toe black, down to black latex gloves. No mask, so they weren’t a COVID thing. I unpacked my suitcase, fumbled with my “universal” outlet adapter, and wondered where the hell Louis found these people.

Detail of Judith Leaving the Tent of Holofernes.

The painting identified in Interview, Palma Vecchio’s Adoration of the Shepherds with a Donor (1520–1525), is—perhaps strangely—not one whose model is traditionally identified as de Romanus’ Amadeo. The real-life donor (commissioner) of the painting who did model for it is, however, unknown—conveniently for Molloy’s purposes.

Detail of Adoration of the Shepherds with a Donor.

As Daniel points out, the dates don’t line up, but I’m not quite ready to say that this means the story is necessarily a lie. It would have been very easy to name-drop a painting whose model is known, and the name Amadeo needn’t have come up at all. The details that do, or at least can, fit and yet are left unremarked upon feels very intentional. The inconsistencies? I mean, Facebook Memories constantly informs me I cannot remember with any accuracy when things happened, and I’m working with 30 years here; if I was 500+, there’s no doubt in my mind I’d be over- or under-shooting recollections by decades, absolutely no malice required. If Armand was born in 1508 and Vecchio painted Adoration of the Shepherds with a Donor in 1525 (the far end of the generally agreed-upon date range), he would have been seventeen—not too far off from the reported twenty. He could have been lying about his age to soften the horror of the story. He could have been recalling a different work, or conflating two separate times he modeled for Vecchio. He might just be very bad with dates—Daniel describes Armand in his guise as Louis’ personal assistant referring to de Romanus as a contemporary of Tintoretto, who would have been just shy of sixteen when de Romanus died (but on the other hand, I’ve seen suggestion that Tintoretto may have been one of Marius’ students in his youth).

Or… given Armand’s skill at memory alteration and hypnosis, and the seeming contradiction of knowing the (*Daniel Molloy voice* alleged) circumstances surrounding his enslavement while his earliest memory is of slavery, I can’t help but wonder if it was a trick he learned from his maker working it on him first. How old was he, when he was enslaved? “His first memory” implies something like three or four, but being sent by his parents to work, even in the medieval period, would suggest to me he was at least seven. The wording is ambiguous, too: did Armand mean that his parents knowingly sold him into slavery and he was lied to when told he was being sent to work on a merchant ship, or that his parents sent him to work and didn’t know he would end up enslaved? The part of me that loves tragedy and melodrama wonders if it’s the latter and the gaps in Armand’s memory are there because the vampire Marius excised any happy memories his beloved Amadeo could have clung to in order to more fully occupy the role of savior—the best, kindest thing Armand had ever known.

Ultimately, we don’t (and won’t) know. A sequel would surely clear up some of our questions with more documents from the vampires’s private archives, but assuming any of this is true, short of Marius de Romanus coming back to life and sitting for a polygraph, Armand’s recollections will be all we have to go on for a lot of his past, and, well… memory is a monster.

I guess this is the part where we talk about historical feasibility? Obviously, truth is stranger than fiction, and there’s always going to be edge cases in the real world, but for our purposes: just how realistic is Armand’s tragic backstory?

Judging by the number of retweets/reblogs on this post and others like it, fannish opinion seems to be “not very”. But honestly? It’s not that far-fetched. Let’s look at what we know from Interview about Armand’s life before he met Louis, operating under the good faith assumption (I know, I know) that he’s telling the truth to the best of his knowledge:

1. Whether he was born in 1508 or as early as the 1480s, he would have been born during the Lodi dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate. Whether he lived in the city itself, in a nearby town or village, or had simply ended up in Delhi at some point before ending up in Venice is unclear.

2. He was sold or potentially abducted at a nonspecifically young age, and remembers a boat.

3. Marius de Romanus purchased him from a brothel when he was fifteen years old. “Amadeo had a skill” seems to imply that he’d been engaging in sex work while owned by the brothel, but it’s not technically stated explicitly.

4. He may have been turned into a vampire in 1508, or sometime between 1527–1532, if we take both the traditional dating of Palma Vecchio’s Adoration of the Shepherds with a Donor and Armand’s story as roughly accurate. Since there’s already inconsistencies here, I’m not going to put too much stock in this: we should just mind that the human lifetime we’re looking at could be anywhere between c. 1481–1532.

5. Louis sometimes calls him “Arun”, generally (and maybe exclusively?) in the context of their whole 24/7 TPE dynamic they’ve got going on. In all but two exchanges in the novel where the name is used, Armand calls Louis “maître” (French for “master”) in return; in the remaining two, Armand does not speak. We’re not explicitly told the significance of this name, but the fandom seems to have generally agreed Arun is the name Armand used before Marius named him Amadeo, and that’s the impression I got when reading as well.

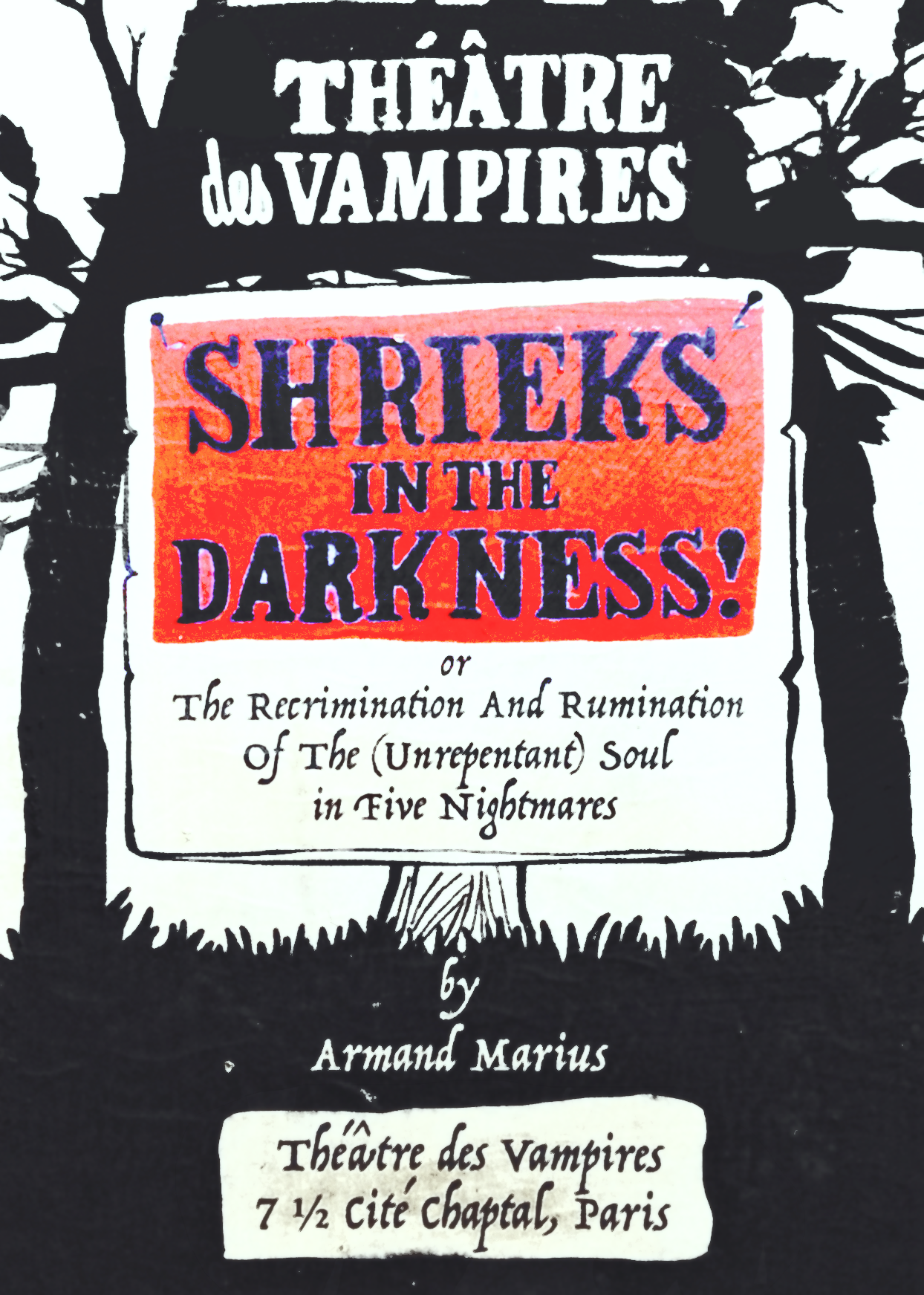

6. By 1556, he was coven master in Paris, and the Théâtre des Vampires was established in 1795. While I’ve seen people questioning the first half, neither Daniel nor the least credulous members of the fandom seem to doubt that Armand was involved with the TdV when it was first established. Daniel finally provides archival documentation to support Armand’s story as of 1928, with a production poster listing “M[onsieur] A. Maurius” as director.

Poster for Rivière du Sang, Faible Courant, first performed Jan 9, 1928.

Poster for Shrieks in the Darkness!, first performed Nov 18, 1946.

Now that we’ve established what we know and what we can reasonably assume, let’s bring in some real-world context.

These days, most of the population of Delhi is Hindu, but at the turn of the 16th century, Islam was the state religion. Armand’s mother tongue would have most likely been Hindavi, an early form of Hindi-Urdu written in Persian script. When recounting his history with Lestat, he says that French was his fourth language, and I’d personally argue that languages two and three were Persian and Venetian (or very possibly the literal Lingua Franca), in that order. I say Persian and not Chagatai (the other official language of the Timurid Empire, and predecessor to Uzbek), which @handinunl0vablehand identifies as the language Armand is likely speaking in this excerpt from chapter four—

Louis sometimes slept in, or “had no choice but to yield to the narcoleptic pull of the sun”, as the chronically overdramatic undead put it. While he was asleep, Rashid would leave me in the reading room with Claudia’s diaries and wander off to do chores and pray to the god who wasn’t fucking him six ways to Sunday.

“How does Muhammad [ ] feel about vampires? Is it Ashura every day in the penthouse?” I asked him one afternoon, spurred to action by the call to prayer for what he called something like “Aser nemozi”—what language it was, I don’t know. I’d waited for him to finish the Tasleem before I interrupted, because I wasn’t raised in a barn, but not to stand up, because I was an ass. Head still turned towards his left-hand angel, Rashid rolled his eyes, sending me straight back to the 90s, when my eldest was going through a “connecting to her culture” phase—which meant her mother’s culture, since she was seventeen and hated me and her stepmom pretty much equally. Alice wasn’t around to hate.

] feel about vampires? Is it Ashura every day in the penthouse?” I asked him one afternoon, spurred to action by the call to prayer for what he called something like “Aser nemozi”—what language it was, I don’t know. I’d waited for him to finish the Tasleem before I interrupted, because I wasn’t raised in a barn, but not to stand up, because I was an ass. Head still turned towards his left-hand angel, Rashid rolled his eyes, sending me straight back to the 90s, when my eldest was going through a “connecting to her culture” phase—which meant her mother’s culture, since she was seventeen and hated me and her stepmom pretty much equally. Alice wasn’t around to hate.

—or Arabic for a couple different reasons. Firstly, Daniel noted that Armand, both as Rashid and as himself, seemed to primarily speak and read Persian or Urdu (according to both the AI translation app on Daniel’s phone and members of the staff) when Louis was elsewhere, but spoke to bilingual Arabic/English staff members in English. This preference would suggest greater comfort/familiarity with Persian than English or Arabic, though he was fluent in both, and was apparently so obvious that in the above excerpt Daniel presumes “Rashid” is Shi’ite.

(“But Noor,” I can hear you saying, because you’re from, I don’t know, Reykjavík, and all you know about Muslims is that they don’t drink, “what makes you say that?” And the answer is that “Every day is Ashura, and every land is Karbala” is a famous Shi’a quote, usually attributed to Imam al-Sadiq  . For Shi’ites (who make up about 13% of the world’s Muslims, mostly concentrated in Iran), Ashura is a day of mourning for the martyred Imam Husayn

. For Shi’ites (who make up about 13% of the world’s Muslims, mostly concentrated in Iran), Ashura is a day of mourning for the martyred Imam Husayn  . Daniel’s jab references the controversial practice by some Shi’ites of tatbir or blood matam, which is a kind of ritual self-harm. I know he self-describes as a shitty husband and father, but given Molloy’s first wife, eldest daughter, and grandchildren are all Sunnis, and he did extensive freelance reporting on location in Tehran in the aftermath of the July 1999 student protests in response to the government shutdown of reformist newspaper Salam, I feel like he’s probably well enough informed about the differences in Sunni and Shi’a practice it’s worth taking this into account? I recognize the irony of saying this when he doesn’t seem to recognize Sunni namaz, but turning your head or not also probably isn’t the most obvious tell for a Christian.)

. Daniel’s jab references the controversial practice by some Shi’ites of tatbir or blood matam, which is a kind of ritual self-harm. I know he self-describes as a shitty husband and father, but given Molloy’s first wife, eldest daughter, and grandchildren are all Sunnis, and he did extensive freelance reporting on location in Tehran in the aftermath of the July 1999 student protests in response to the government shutdown of reformist newspaper Salam, I feel like he’s probably well enough informed about the differences in Sunni and Shi’a practice it’s worth taking this into account? I recognize the irony of saying this when he doesn’t seem to recognize Sunni namaz, but turning your head or not also probably isn’t the most obvious tell for a Christian.)

I’m also not entirely convinced it’s Chagatai عصرنموزي (asr namozi), and not Armenian ասր Նամազը (asr namazy), but explaining why right now will make me look like an insane person. They both come from the Persian word namaz, which is the preferred etymology over Arabic salat in most languages spoken in Muslim Asia, including Hindi-Urdu, Russian, and even Mandarin Chinese. Armenian in particular has… potential implications. But whether it’s Chagatai, Armenian, or one of the likely many minority languages/dialects who call the ‘Asr prayer something very similar, there’s a third reason why I think Armand’s L2 is Persian, but we’ll come back around to that later, because, again, I’ll sound like an insane person. Put a pin in it. Back to Delhi.

During the Delhi Sultanate’s Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1413), the city had an estimated total population of 400,000, and of those, as many as 180,000 were slaves. Slaves were acquired variously through conquest, child-selling and child abduction, the proliferation of slave families and houseborn slaves, and the enslavement of non-dhimmi (a protected citizen category including Christians, Jews, and occasionally some other minority religions) households and villages who failed to or were unable to pay their taxes.

The bulk of slaves bought and sold in Delhi had been trafficked domestically—unlike in the Timurid and Mamluk markets, where Ukrainians and Ethiopians could be sold side-by-side and most slaves at market had been imported (our limited documentary evidence suggests the sale and purchase of houseborn slaves could occur rather informally, without involvement of a professional slave broker).

In theory, Muslims were forbidden to be sold as slaves. In practice, many slaves were Muslim, whether they had converted to the faith or were born into it, theoretically as houseborn slaves or Shi’a “heretics”. We see acknowledgement of this reality in ibn Bassam’s 14th century ḥisba manual, which instead only bars the sale of a Muslim or any child whose mother was not a devout Christian—and therefore would presumably raise her child Christian—to dhimmi. Sale of Muslims or children to other Muslims, assuming they were either Shi’ite or came by their slave status “legitimately” (i.e., before conversion to Islam or else by birth), was fine. Additionally, manuals from Egypt and Syria, at least, use Arabic fluency as proof of religious affiliation: “those [slaves] who do not understand are Christians”, writes ibn Bassam.

However, even non-Arab Sunnis who were fluent in Arabic (which was not always a given) were not always safe from illicit human trafficking. Al-Sakhawi writes in the 15th century of a Black slave woman called Jawhara, allegedly an Ethiopian Christian, who insisted that she was a Jeberti Muslim by birth and that her given name was Fatima.

Arun is not a traditionally Muslim name. This should not be taken to mean Armand could not have been born or raised Muslim. It has always been a common tactic in systems of slavery to further dehumanize its subjects by stripping them of their personal names, be it in ancient Rome, 11th century Mecca, 19th century USA, or elsewhere. In the medieval Muslim world, where religious background was often the only thing differentiating lawful slavery from decidedly haram trafficking in persons, slave brokers and slave buyers might have additional reason to force “foreign” names upon their victims. Arun is a modern, westernized form of Aruna/Aruni, a dual-sexed figure from Hindu mythology who represents the dawn, as the chariot-driver of the sun. The name must have appealed to Molloy for his androgynous, sun-walking vampire; it would have appealed to Armand’s traffickers for its pagan roots.

I know there’s some discourse about it, but I don’t think Armand’s current faith and practice is at all in question, for all that Daniel is incredulous of his devotion and thinks he’s a hypocrite. We see him make namaz, we see Louis belittle “Rashid” for his metronomic—dare I say…boring—adherence to a schedule that explicitly includes the daily prayers, after Daniel is made an accomplice to murder in chapter eighteen he follows up with Armand about his feeding habits and is treated to “a frankly unhinged argument that blood-drinking [is] not haram for vampires, but only makrooh, or disliked,” and “detailed guidelines for selecting and slaughtering a human victim in accordance with Islamic dietary law” (which I am completely obsessed with), and the book notably ends lingering on Armand’s twofold devotion. Actually, I’m just gonna copy/paste the whole last two pages of the book. You’ll see why later.

Unraveling Armand’s web of lies felt like taking a hit, like winning a fight with my wife—for that five, ten minutes? I’m untouchable, on top of the world. But then cold reality sinks in.

What had I actually achieved? The satisfaction of being right. Managing to chase Louis right back into the arms of the guy who beat on him. My own death by angry vampire, definitely, because now Armand was pleading desperately in the next room over, his voice cracking on an “I love you” that I might even believe. Louis grabbed him by the face and slammed him against the wall so hard the whole building shook. Glass rained down on me from the bookshelves, and the foot-thick reinforced concrete had visible cracks on the opposite side. I lingered in the doorway.

Louis looked monstrous in a way he only rarely did, rage distorting his features; Armand was slumped on the floor like a Raggedy Ann doll, covered with plaster, with bloody claw marks on his face. I suddenly wasn’t sure which one of them was gonna have me for dinner. You fear Armand, my anonymous source had said. You should fear the other one.

I was starting to see why. Louis loomed above his boyfriend. “You’re not to touch him. Do you understand?” A long pause. Armand said nothing. Maybe he was using the Mind Gift. Yes, Maître. “You harm him in any way, I will kill you. Do you understand?”

Again, nothing. Louis told me he’d book me a flight and wire me an incomprehensible amount of money, then offered his hand to shake. His claws brushed the back of my hand. Then he was gone, and I was alone with Armand.

Some stupid, suicidal impulse had me opening my mouth again. “You gonna eat me now, or just mind-rape me again? Let me guess: you can see me still, standing there and saying, ‘Look at this script,’ and staring at nothing.”

I thought he’d keep up the silent treatment, but Armand huffed out a little breath that might’ve been a laugh. “Gaslight, 1944. Louis and I saw it in the cinema in the summer of ‘47—American films had been banned when Paris was under occupation, you see, and there was quite the back catalog to get through after the Blum-Byrnes agreement was signed. I liked it well enough, though I rather prefer the 1940 production, myself.

“But no, Mr. Molloy. I did indeed direct The Trial. Louis did not know. It was… simpler, that way. He already believed me a coward, and hated me for it, even when he loved me; whether he knew the full extent of my shame changed little.”

“You-shaped hole in the wall begs to differ.”

“You cannot judge eternity on a single moment of temper. This is not the first time Louis has left me, nor will it be the last.” He didn’t say anything else, didn’t so much as move a muscle, until dawn broke and the call to prayer rang out.

Armand’s parents, as far as he recollects, were not enslaved alongside him, which would rule out several of the common modes of enslavement in the period. Assuming he’s right, I see a couple different options here:

1. His parents were free Hindus who sent him to work or sold him to a merchant.

2. His parents were free Muslims and sent him to work for a merchant, expecting his religion to protect him from enslavement.

3. His father was a free Muslim and his mother enslaved; when Armand, houseborn, reached the age he could be legally separated from his mother (al-Shayzari says this is age seven), his father sold him to a merchant.

4. His parents were Mallahs or merchants themselves, regardless of religion, and he was perhaps sold or abducted.

I suspect that either Armand’s father or one of his early owners was a dervish, and the early exposure to Sufism was greatly influential—in part because of something I’ll get to later, in part because Armand’s description of a fledgling Lestat as “a patronized, tarted-up dervish” is… definitely projection, right? It’s a very weird thing to say about a French Catholic stage actor. Armand is identifying the young and bold Lestat with the parts of himself that he felt had been lost in centuries with the Children of Darkness—perhaps identifying him with Amadeo specifically. He’s not so much calling Lestat a dervish as he is calling himself (or a version of himself he simultaneously despises and longs to become again) one.

Now, I keep saying he was probably sold (or born to) a merchant because of that detail about working on a boat. Multani merchants (who could be either Hindu or Muslim—even some Sufis were involved in the slave trade) would have been involved in the Yamuna river trade route connecting Delhi to nearby Agra. There’s an off-hand comment from Louis, too, that “[Armand] sometimes lingers when boats come into harbor”, which—if it’s not PTSD—could suggest an affinity for the water. “Rashid”’s daily swim (presumably something Armand actually does, as specific a detail as it is and Louis being such a poor liar) supports this interpretation, I think. I have to wonder if Armand is originally from the Mallah caste, who are boatmen and fishers by tradition. Mallahs are SC in Delhi (i.e., Dalit/untouchable): still working on the river but for a travelling merchant might have been seen as an improvement of circumstances by Hindu parents, and despite the fact caste is not recognized by Islam (a fact which is held to have helped lead to the largely backward caste demographic of Indian Muslims), casteism was alive and well in the Delhi Sultanate and may have been a factor in Armand’s victimization, were he born a free Muslim.

Whatever the case may be, either his memories are unreliable (due to trauma, simple age, or intentional alteration by his maker or another powerful vampire), or he changed hands multiple times between his initial enslavement and his purchase by Marius de Romanus, because the international trade routes with Delhi were all at least partially overland, and while we’re not told what city de Romanus bought him in, I can find nothing to support de Romanus having taken a trip to India, and that’s just not Molloy’s style. Caravans went north from Delhi through the Himalayas on the Silk Road trade route, or west to Cambay for the sea trade. The northward route is a likely suspect if he was purchased by de Romanus while the latter was still living in Samarqand (prior to 1498); Cambay is a reasonable guess for purchase in Alexandria, or in Venice proper.

The question then becomes: which?

Unfortunately for us, the Venetians did not keep a state register of all the slaves sold at the Rialto (which amounted to several thousand per year) like their Florentine neighbors did, so we can’t either confirm or rule it out with their gorgeously near-comprehensive state archives. And I did try, okay. I read so many horrifically upsetting court cases for you, you have no idea. Which brings me to the fact I think Venice is the least likely city for Marius to have bought Armand in. It’s not impossible—crimes go unpunished everywhere, and the archives are only nearly comprehensive—but the Serenìssima had very strict laws in place regarding both prostitution and homosexuality.

I’d expect “““illicit””” sexual abuse to slip through the cracks in a private house (there is in fact a case from 1368 where a man whose sodomy conviction was complicated by erectile dysfunction—intercrural and anal-penetrative intercourse were handled differently, and he had tried but failed to penetrate his partner—admitted when questioned to having years earlier repeatedly sexually assaulted a Saracen (that is, Muslim) slave boy “whose name he no longer remembered”; though the boy was owned by another family, no case was brought by them), as in Armand-as-Amadeo’s description of being (for lack of a better word) loaned out to de Romanus’ friends. The brothels, however, were highly regulated, madams and sex workers alike subject to intense scrutiny for fear girls might be forced to remain in sex work due to debt or other circumstances. If there was any formalized slave prostitution in 15th and 16th century Venice (I will freely admit that my familiarity with Italy plummets after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and while this book pushed me to do a lot of research, I might still have blind spots) I’ve found no evidence of it. The girls working in the brothels were largely foreign, yes, but they were free.

As we frequently see in slaveholding societies, while the sexual availability of a slave to her owner was perfectly ordinary and expected by Venetians, forcing her into sex work was considered perverse and degrading—a moral injury. For the same reason, we find some ancient Roman slave contracts with verbiage voiding the sale if the buyer forces the slave into sex work. In the Muslim world, though slave concubinage was customary, the prostitution of slave girls and women (but not boys) was banned altogether.

The closest thing I could find to evidence of formalized male prostitution in Venice during our period is a single instance of an assigned male intersex individual named Rolandina Ronchaia living and working out of a brothel as a woman; when she or they were discovered, the case went to the Signori and Ronchaia was sentenced to death.

A sodomy conviction in Venice, in the case of penetration, meant execution (typically by burning) for the active partner; the passive partner was, after benchmark legislation in 1424 which removed protections for young boys, subject to a minimum of three months in jail and twelve to twenty lashes, with stricter penalties imposed for passive adults and older teens, or if the council deemed it otherwise warranted due to the particulars of the case. Sixteen-year-old Carlo Bomben was tortured and mutilated during his six month stint in prison; ten-year-old Aloysio Maronerti, for the crime of having been gang-raped, was in 1474 let off with the particularly light sentence of only ten lashes. Though there was always gossip, Marius de Romanus was apparently never accused by any of his apprentices or slaves of sexual abuse; given this context, it’s easy to imagine why that might be. I feel like I should mention here that Marius de Romanus died in a fire at his palazzo in 1535. Bianca Solderini, a local courtesan, in writing to inform a mutual friend in Florence of his passing, said:

Oh, poor Marius! And those poor boys of his! I pray they had the good fortune to pass in their sleep, a painless smothering like returning to the womb. They did not deserve such an awful fate! I wonder who set the fire? An enemy of his, perhaps, though it is difficult to imagine someone counting our dear Marius an enemy. I only hope it was not—well, you know. He could have his outbursts. Always a spirited one, our beautiful friend, but I do not think there is evil in his heart.

Translated from the Venetian by ohamadeo over on dreamwidth, to whom I am unutterably grateful. Go check out her journal—she’s got great meta and even better fics. If anyone could convince me Interview is nonfiction, it’s her.

Now, not every case presided over by the Council of Ten (which typically oversaw sodomy cases in our period) survives: it’s entirely possible Molloy means to exploit one of these gaps in the record to place the shutdown of an illicit brothel and subsequent trial of both victims and perpetrators, Marius de Romanus charitably taking in an abused slave with nowhere else to go. It’s also possible a brothel operated successfully on the fringes of polite society, paid off their favorite barber/surgeon (who were legally mandated to report suspected sodomy-related injuries in women and boys), and alleged Armand-as-Arun was a girl domestic (or "ancilla") when the Capisestieri came knocking. But when I hear hoofbeats, I think horses, and it is much, much easier to come by a brothel employing boys and eunuchs in Alexandria or Samarqand.

Safavid Iran (successor to the Timurids) in 1501 was taxing and regulating perfectly above-board amrad-khane, literally “boy houses”—brothels catering to a pederastic clientele. Arabic and Persian poetry throughout our period describe boys and eunuchs as objects of sexual desire. Al-Ghazouli, a fifteenth century author in Damascus of slave origin, in his Matali al-budur copies a muwashshaḥ poem written by Fadlallah bin Maqanis, “[his] master and brother”, the first two stanzas of which read:

copious tears flow from my eyes

like the sea

and in all my years I have never known a stable home

my beloved has abandoned me, he is close beside me

in the company of the guard

he returned to me from an ancient people a stranger

I do not want to falsely give the impression medieval Muslim society was some kind of queer utopia. American sexologist Vern Bullough argues in his Sexual Variance in Society and History that Islam, compared to Christianity, is a “sex positive” religion, and medieval Muslim society one which is largely accepting of homosexuality. This is not wholly incorrect, but it is a reductive claim. Most modern retrospectives on the inclusivity of the past are, honestly. “Homosexuality” as we think of it today is no more readily applicable to 15th century Iran than it is to 2nd century Rome, and neither society would be likely to look kindly on our modern-day equitable love affairs between adult men or adult women. What it is accurate to say is that many men certainly held romantic and erotic passion for boys or eunuchs in the medieval Muslim world, and this was tolerated and even considered beautiful—but some of the same scholars who composed gorgeous love poems for their teenage boy beloveds harshly disavowed liwat, or penetrative anal sex between men, in accordance with Sharia. (Not every Sunni madhhab is in agreement that liwat is a hadd offense, but all agree it’s haram.)

We might be reminded of the Venetian Council of Ten’s similar line in the sand, where—while romance and non-penetrative sex were in their case also a sin—it was the act of penetration which was truly damning. And in both we see an expectation that the active participant, the pursuer, is an adult man, while the passive, the seduced, is a youth or sometimes even prepubescent. In the Muslim world, influenced greatly not only by classical Greek philosophy but also its pederasty, it was understandable for a boy of twelve or fourteen to be seduced, but you ought to outgrow such things. In Venice, while youth did not confer any social acceptability to the practice, it was a mitigating factor in the prescription of punishments, so the pederast’s beloved is positioned as having less to repent for than the adult homosexual.

Now, we know a great deal about the logistics of slave-buying and slave-selling in Mamluk Egypt thanks to the ḥisba manuals written for marketplace inspectors, and thanks to the Venetian state archives we have examples not only of slave contracts worked up in Latin or Venetian by Venetian notaries but also those worked up in Arabic by Alexandrite notaries for Venetian buyers. Very good English translations of the Latin contract type are already freely available, so I won’t reproduce one here, but the Arabic I know of only translated into French, so here is an example (reproduced from Bauden, “Lʼachat dʼesclaves et la rédemption des captifs à Alexandrie dʼaprès deux documents arabes dʼépoque mamelouke conservés aux Archives de lʼÉtat à Venise (ASVe)”):

The consul Biagio Dolfin, son of Lorenzo, consul of the community of the Venetian Franks in the protected place of Alexandria, purchased with his own money for himself from the priest Youhanna, son of the bishop Balta, son of the priest Shenouda the Jacobean Christian, who sold him what he mentioned was in possession in his hand and at his disposal until the [present] date, that is, the whole Nubian slave called Mubarakah, a woman, Christian, known to both of them per the law, by an authentic and legally binding deed of purchase, [and] declared free of all defects proper to slaves, for a price whose amount for the aforementioned slave in Venetian gold ducats of full weight is 27 ducats, half of which, which preserves the document, making in all 13 ½ ducats of the aforementioned kind, the whole of the price having been received by the seller who acknowledged this with his witnesses, who witnessed this with their own eyes. They both entered into a legal agreement on this for this by offer and acceptance. The aforementioned buyer has legally received the slave here sold and this after he had examined her and appraised her so as to deny all ignorance, the claim on this matter, where it is required, being legal. The two contracting parties have agreed by virtue of an executable agreement that the aforementioned price is exempt from tax since it falls on the purchaser. Witness has been taken from them, who act of their own free will and on their on initiative, sound and in a state of legal capacity, on the date of 22 Safar of the year 822.

Below these are the signatures and attestation of the two witnesses. At the top of the document is written the Basmala, which I prefer not to reproduce in the context of a slave sale. On the reverse, written in Venetian: “Written document of the black slave girl I purchased March 20, 1419 in Alexandria.” (Mubarakah is described in the contract as “whole” because co-ownership in Mamluk Egypt was expressed with contracts selling a slave subdivided into 24 parts, so that, for example, a husband and wife might each own twelve parts of a slave girl.)

This is a somewhat abbreviated contract: ḥisba manuals provided formulas for the information a slave sale document should impart, namely whether a slave was Turkish or black (only the former were considered appropriate for military service), their race, religion, age (adult, adolescent, ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, weaned, or suckling), sex, the name they were called by, their acknowledgement of their bondage and servitude (if they were an adult), and a physical description. Al-Asyuti offers as an example of the last, “He has a brownish-black complexion, short and curly hair, soft cheeks, a handsome face, and a harmonious stature.” Black slaves, definitionally, were divided among eleven races: nine different African ethnicities, Indians, and houseborn slaves (regardless of their actual skin color or heritage).

I would not be at all surprised to see a document like this or the above linked Venetian notary’s (sadly, from our period no slave sale documents from Samarqand survive) reproduced in Molloy’s next book, sourced from the archives of his much-beloved fictional Bibliotheca Talamasca. The artist Marius, son of Marius, purchased with his own money for himself…the whole black slave of Hindustani race called Arun…

Unfortunately, we can’t look to Amadeo to provide us many answers. Ohamadeo’s incredibly helpful compilation of every attestation and potential allusion to de Romanus’ muse in the historical record provides some fascinating tidbits, including the letter above by Bianca Solderini (could “our beautiful friend” have been Amadeo?), and another from some 40 years earlier, in the diaries of Giovanni Antonio Barbaro, son of the travel writer Giosafat Barbaro:

Reaching Sanmarkan in June of 1496, for eight days we stayed with Marius the Christian, who was known to us, for every Venetian or Genovese who had journeyed so deeply into Persia sung his praises as a host. He was an artist and a merchant of perhaps Spanish extraction, with golden eyes, and as a host he was indeed without fault. He kept a handful of boys about him always, some students of his (for he was a painter of great skill) and others without obvious purpose. One evening he offered to me for the night one of the latter, dark of face and almost entirely silent, who was apparently skillful. His kind, Marius said, were naturally accustomed to use, like women, and among the Saracens such things were not thought unnatural.

These and other quotes certainly provide food for thought and fanfic (if you’re inclined to an extra shade of horror, check out this chatlog with ohamadeo I posted a couple days ago), but very little in the way of dates or locations. Of Amadeo’s background, even less is known than his master’s. He was a slave or perhaps had been manumitted, understood Venetian “well enough” around 1518–20, was wholly devoted to de Romanus, and presumably died with him in 1535. The Temptation, de Romanus’ most famous work which Amadeo is known to have modeled for, was not painted on commission; this combined with de Romanus’ notably stagnant artistic style, and of course the loss of the original, complicates its dating. It must have been painted in 1498 or later, for it depicts his muse in Venice overlooking the canals, but beyond that it is anyone’s guess until 1522, when the painting is first described by Paris Bordone.

Many other portraits suffer the same problem, and the matter is additionally complicated by the suggestion that “Amadeo” was not a single individual, but rather an affectionate name given to de Romanus’ favorite young muse in whatever year: while Amadeo is invariably depicted as a youth with dark curls falling past his chin, his other features are “in flux”—a strange trait, Burckhardt noted, in the work of a man infamous for lack of embellishment. Even Amadeo’s skin (typically pale) is not constant, if a certain student copy of The Temptation ohamadeo tracked down can be trusted. Against tradition, she also claims another de Romanus as a painting of a dark-skinned Amadeo, and I agree with her here—or at least, I agree that Molloy intends it to be taken as such.

Remember all those things I said to stick a pin in? It’s time to go back to the pinboard now, because what struck me most of all when I first read Interview with the Vampire was how clearly Armand was based on Daniel Molloy’s first wife.

Now, I don’t know how many people in this fandom have read Molloy’s other books, but let’s pretend you know nothing about him for a second. Daniel Harutyunan Molloy was born May 5, 1953 to Lena Harutyunan Molloy; his father, Karen Harutyunan, Lena’s first husband, died before he was born. Both were Armenian Christians, Karen having been two years old when his parents fled the ongoing genocide, and Lena’s mother pregnant with her. Karen’s best friend and Daniel’s intended godfather Declan Molloy married Lena when she was eight months pregnant: they apparently remained “close friends” until Lena’s passing, and never had children of their own. Molloy grew up in a culturally Christian but largely agnostic household in Modesto, California, feeling equally out of place in the Armenian community and apart from it. He still “only half speaks” the language, a serious attempt to finally become fluent in the late 70s almost completely wiped out by a haze of drugs. He’d left home at eighteen to find himself in San Francisco; what he found was the counter-culture, and eventually a job as a stringer with the Berkeley Barb.

In late ‘73 or early ‘74, twenty-year-old Molloy met Alice Maripor. They never legally married, but Molloy always calls her his wife. A neo-expressionist painter and likely sex worker, Maripor was born in Delhi and left orphaned and violently displaced by Partition, which saw 330,000 Delhiite Sunnis flee to Pakistan or Bangladesh and an estimated 20,000 killed. She’d been in San Francisco for a few years when they first met: Molloy tried to interview her, he recounts in his memoir, “and I swear she came this close to gutting me like a fish. It was the sexiest thing that’d ever happened to me.” I don’t think anyone thought he meant she was literally murderous when Hate & Ashbury first came out, but after that Divisadero chapter, who fucking knows, man.

A couple things I should get out of the way right off the bat. First of all, for a while in ancient Rome there was a trend of giving slaves personal names that literally translated to “[owner’s name]’s boy”. A man called Gnaeus might have a slave named Gnaepor. A man called Marius could have called his slave Maripor.

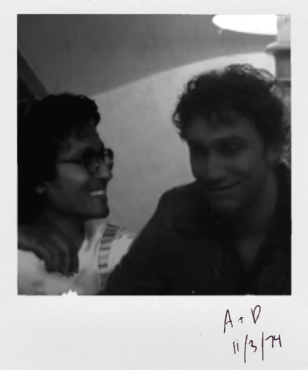

Second, I want you to look at this photo of Maripor and Molloy:

In case you’ve forgotten, here’s the photo we’re told Louis took of Armand in 1946:

So. There’s that.

Maripor was a bit older than Molloy (and thus always knew better), and insisted on financing what she called Molloy’s “enculturation”. He called it “getting dragged around half the planet by [his] dick” live on CNN once, before admitting that he wouldn’t have become half the reporter he was if he’d stuck around in SoCal snorting coke that whole time, “so I guess she really did know better.” It’s a wild interview.

Their first daughter, Kate, was born in 1976. These days she’s a middle grades graphic novelist with awards of her own. Their second, Lenora, was born in ‘85 and stays out of the public eye. In June 1987, Maripor walked out on a fight about Molloy’s continued drug use and never came back. Kate, nine years old at the time, recalled in a 2017 blog post her mother’s frigid hands, constant exhaustion, and the way Kate never, ever saw her eat:

In hindsight, I think she was dying. At my lowest, I hope she was, because that means she could have still loved me. It means she would have come home, if she could.

In October 1987, five days after the AIDS Memorial Quilt first went on display and two weeks ahead of Randy Shilt’s And the Band Played On, Molloy’s first book was published. A Shadow on the Skin chronicles the AIDS epidemic from the first reported cases of Karposi’s Sarcoma to the March 1987 FDA approval of azidothymidine (AZT), the first antiretroviral medication for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Unlike Molloy’s later books, which combine autobiographical elements with his investigative reporting much like Interview with the Vampire purports to do—his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Homelandia, for instance, ties in his diasporic upbringing as he tackles the question of what makes a national identity—A Shadow on the Skin humanizes its subject entirely through interviews with AIDS patients. Molloy’s personal ties to the crisis—as an IV drug user and MSM living in San Francisco in the early years of the pandemic whose wife’s artwork directly addressed the HIV/AIDS epidemic—are left unremarked upon.

The fictitious Amadeo did not burn to death in his master’s palazzo in 1535. He was given the Dark Gift at age 27, dying, says Daniel, of an unspecified illness. In 1949, he told Louis he had not been painted in 400 years. And in 1987, an art exhibition collecting the work of “A. Maripor” titled O, AMADEO—yes, really—ran from April 10–May 20 in “The Basement”, an LGBT-centered art exhibition space in SoHo that would later become the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art.

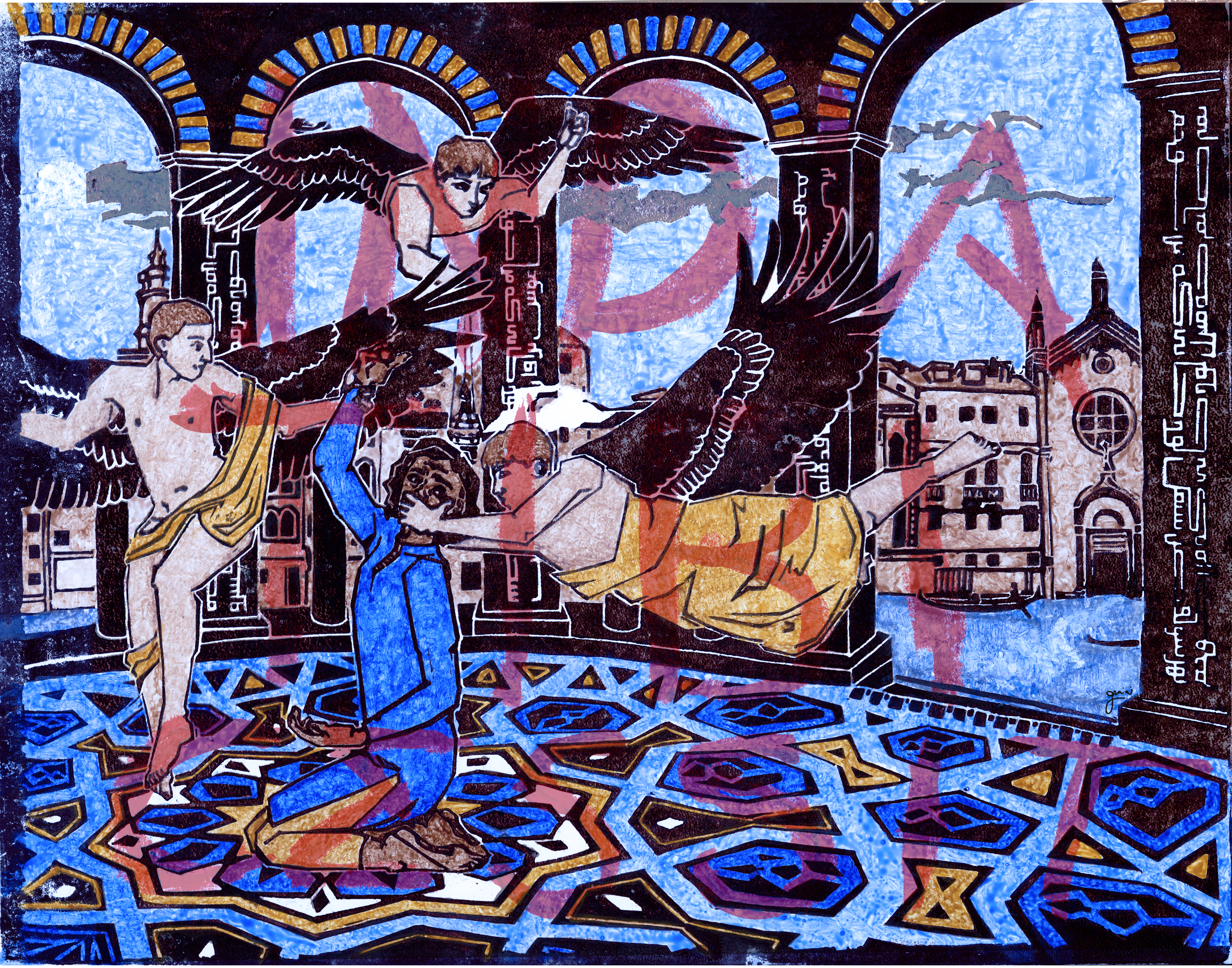

A few of the paintings from this exhibition are now a part of the Leslie-Lohman’s permanent collection: the most well known is probably The French Disease (1985). The mixed media painting (linoleum block print and egg tempera on panel) depicts a teenage prostitute bedecked in a Renaissance gown and disfigured by tertiary syphilis twisting open the cap of a prescription pill bottle. A real label affixed to the painted bottle reads AZIDOTHYMIDINE 1200MG. It’s a stunning painting on both a technical and emotional level, but more of interest to us are INDIA TIBI CESSIT (1982) and Self-Portrait, or Slave Boy with Severed Head (1987).

“India tibi cessit”, Latin for “India yielded to you”, was inscribed beneath a no longer extant fresco of St. Thomas painted by Paolo Uccello around 1490, but Maripor’s painting is not of St. Thomas—it’s appropriation art based on The Temptation of Amadeo. Several thousand words ago, I mentioned that while the original de Romanus was lost in the 1860s, a few copies made by his apprentices survived, but never actually showed you any. Here’s the one ohamadeo found so interesting:

[FULL SIZE]

Approximately 11 by 14 inches, the painting is egg tempera on panel, and is unfinished, with the underpainting partially exposed. In the lower-right corner of the panel we can see the artist’s signature: Riccardo. Ohamadeo hasn’t found any mentions of an apprentice painter named Riccardo in the correspondence or writings of de Romanus’ known associates, but my deep dive into the ASVe turned up a record of his sale to de Romanus in the logbook of a Venetian notary. Heavily abbreviated, it lists Riccardo as a verna (houseborn slave) “of Ethiopian race” purchased June 7, 1499. Sadly, his age was not provided.

By and large, Riccardo’s student copy of The Temptation matches the descriptions of de Romanus’ original with the exception of the more photorealistic elements (paintbrushes and dead leaves) in the original composition. The central figure, Amadeo, kneels in the center of a geometric mosaic that would not look out of place in the Shah-i-Zinda, barefoot in a loose chemise and hose with right hand upraised. Glancing over his shoulder, he seems to give the viewer a coy look. At Amadeo’s back, on the opposite side of the canal as seen through the tiled archways, is the facade of the Madonna dell’Orto and above it the sun. Surrounding him are three black-winged angels, reminiscent of mannerist depictions of the assumption of the Virgin. Two of the angels hold aloft a blue stola, ready to drape the cloth over Amadeo’s shoulders, and with his free hand one of the angels makes the Christogram IC XC, used—notably—in the Orthodox tradition. The composition leads one to wonder if Amadeo is being tempted by the black-winged angels into Orthodox “heresy”, or if—with his back turned away from the Church and the light of the sun, with the almost flirtatious look on his face—the temptation of the title is Amadeo himself.

The greatest difference between the copy and descriptions of the original is revealed by the underpainting. In the completed portions of the painting, Amadeo, though dark-haired and dark-eyed, is as pale as the angels surrounding him. In the underpainting, his skin is a much darker value. Either the model who sat for this painting was dark-skinned, or Ethiopian Riccardo chose to paint him as such before (presumably) his master made him “correct” his work.

This version of The Temptation, or the metanarrative of its creation, becomes particularly compelling in conversation with Maripor’s.

[FULL SIZE]

Likewise 11 by 14 inches, INDIA TIBI CESSIT (which is writ large across the canvas with messy, violent smears of pure, poisonous vermillion—the only use of red in the painting, otherwise limited to a palette of cobalt, yellow ochre, and titanium) is linoleum block print and egg tempera on panel and its composition is very similar, though the style is radically different: as in The Temptation of Amadeo, the central figure kneels, back to the Madonna dell’Orto, on a Timurid mosaic. Black-winged angels surround him. One makes the Christogram IC XC. What has changed, however, drastically recontextualizes the artwork. Where The Temptation’s angels are respectful and ready with a robe of Marian blue to drape over Amadeo’s shoulders, Maripor has depicted them as a violent presence. One has a bruising grip on the wrist of the central figure (dark-skinned and dressed in a salwar suit), yanking it up over his head, which has the effect of suggesting that Amadeo—kneeling with cupped hand(s) oriented skyward—had been making du’a.

Rather than glancing coyly at the viewer, Maripor’s Amadeo appears terrified, and with good reason: another angel has his hand clamped over Amadeo’s mouth. The image invokes the crossing of the Red Sea, where the angel Jibreel  at the command of God

at the command of God  put a handful of mud in the mouth of the Pharaoh so that he could not say la ilaha illa Allah (and so be granted mercy) as he was dying. The third angel, the one making the Christogram with one hand, here holds a Catholic thurible in the other. Finally, and very significantly, Maripor replaces the original geometric tilework on the columns of the archways with square Kufic calligraphy. Though partially obscured by the figures in the foreground, enough of the calligraphy is visible that the source can be identified as Nami danam che manzil bood:

put a handful of mud in the mouth of the Pharaoh so that he could not say la ilaha illa Allah (and so be granted mercy) as he was dying. The third angel, the one making the Christogram with one hand, here holds a Catholic thurible in the other. Finally, and very significantly, Maripor replaces the original geometric tilework on the columns of the archways with square Kufic calligraphy. Though partially obscured by the figures in the foreground, enough of the calligraphy is visible that the source can be identified as Nami danam che manzil bood:

I don’t know where I was last night.

Sacrificial victims of love were dancing where I was last night.

A painting come alive, slim and tall as a cypress, with tulip-red lips

Broke a thousand hearts where I was last night.

Rivals hung off his every word. He was coy, and I so afraid

It was hard to even speak where I was last night.

God is the master of ceremonies there in the heavenly court

and the Prophet our candlelight, where I was last night.

This classical Persian ghazal was written by Ameer Khusrau (1253–1325), who founded the Delhi gharana, and if Persian being the official language of both Delhi and Samarqand, and certainly one Marius would have been fluent in, wasn’t enough to convince you it’s Armand’s L2, maybe Alice Maripor’s obvious familiarly and connection to it is. Armand could have very easily known this very song as a child, which remains a favorite for qawwals (Sufi dervishes who sing devotional hymns in the qawwali style) today.

The second piece by Maripor I want to bring to your attention is, once again, appropriation art of a Marius de Romanus. (You’re getting a very heavily curated taste of her work here, by the way. I feel like I should say now that like eighty percent of her work—and where I first stumbled across her—is either, like, technofuturist fetish art or oil paintings of small kitchen appliances? Before you go looking her up hoping for more Renaissance paintings and instead find a lot of lovingly rendered androids getting cigarettes put out on them. Or blenders.)

Slave Boy with Severed Head (1533) is probably best described as, uh, “before its time”. I also wouldn’t recommend clicking that link if you're at work or on public transit. A striking and relatively simple portrait painted in oils with large, bold strokes, the painting depicts a dark-skinned and beardless youth reclining in an armchair, holding the severed head of a elderly white man by the jaw. It is too lazy a pose, too sensual, to consider the painting a twist on Judith: this is not a triumph, and despite the blood on his hands and the lower half of his face (almost as if having taken a bite out of his victim), the eponymous slave boy is more object than actor. He, unlike Judith, has no sword in hand, and he presents us this monstrous trophy almost as if daring, “Punish me.”

Wearing golden rings set with large gemstones, the slave boy is nude apart from a length of gauzy Dhaka muslin, the drape of which across his thighs does not prevent us from identifying him as Muslim by his circumcised penis. Striking honey-gold eyes lined with kohl do not meet the viewer’s: rather, he gazes towards the bottom-right corner of the frame with the artful indifference of a Vogue model. The work’s overt sexuality is out of place in the Oriental Mode of the Venetian Renaissance, but is good company for the paintings of Étienne Dinet and other 19th-20th century Orientalist artists. The subject is at once passive sex object and subhuman brute, a cannibalistic savage whose subjugation the (white) viewer is invited to fantasize about.

The model for Slave Boy with Severed Head is not traditionally identified as a painting of Amadeo, but the resemblance to Armand/Alice is striking. Maripor certainly recognized it herself, because in 1987 she painted Self-Portrait, or Slave Boy with Severed Head.

[FULL SIZE]

Presently on exhibition in the MoMA on a CRT monitor, Self-Portrait is one of the earliest known digital paintings created with Adobe Illustrator, only days after its release. Harsh geometric linework and neon-bright colors are a dramatic departure from the aesthetic sensibilities of the de Romanus it appropriates, firmly planting Self-Portrait in the modern era. The work depicts its subject—whose masculinity despite being labelled a self-portrait has been interpreted as an extension of the appropriated painting, a commentary on the marginalization of women in the “boy’s clubs” of Abstract and Neo-Expressionism, in a transgender lens, and more—with his-or-her own severed head dangling bloodlessly from one hand. Accompanied by a blood smear on the inner thigh, the stretch of the severed head’s lips around the intrusion of their own fingers is undeniably sexual, and that sexuality is undeniably violent.

Susan Sontag in her essay “On Style” writes:

Art is seduction, not rape. A work of art proposes a type of experience designed to manifest the quality of imperiousness. But art cannot seduce without the complicity of the experiencing subject.

Marius de Romanus asks us to be complicit twice over: first to allow his Slave Boy to seduce us, but second to play the voyeur in the rape that is the art, that is memorialized by it. This is not unique to Molloy’s interpretation of him (or rather, Maripor’s interpretation filtered through Molloy)—we cannot get around the fact that de Romanus owned slaves and subjected them to sexual abuse, that the making of this very portrait was more likely than not itself an act of abuse, the enslaved body made into objet d’art.

We are far more concerned as a society with the photograph as abuse material than the painting: perhaps because we intuit a level of remove, a level of inherent unreality, to a painting that is absent in photography; perhaps because we see painting as art, and photography as archive; perhaps the liminal space the painting-as-abuse-material lives in, where we cannot know it is not imaginary, absolves us of guilt. But of course, in an age of AI deepfakes and Photoshop, can we take the photograph to be any more real or true than the painting? Can we say that a photograph is not art? If we allow the “art photograph” and “archival photograph” to coexist, can we say that the relay of information is not itself art? Richard Shiff writes in “Less Dead”, “With photography, we frame a view, selecting the image from among all that reality offers.” Nothing a human being can produce is truly objective, and anything—the composition of a photograph or an argument, the construction of a mundane tool—can be artful. I wonder what Armand feels when he visits the National Gallery, where this painting hangs today. If there is any qualitative difference between his reality and the mundane horror of photographic abuse material lingering on the internet and on hard drives in perpetuity.

Marius de Romanus’ victims are all long-dead, existing now as fictions—I mean this in the sense that Interview is a work of fiction, of course, but moreover in the sense that any figure from history is by necessity fictionalized to some degree or another in how we transmit the memory of them. There is no one really left to be directly harmed by these 15th and 16th century paintings hung up in art museums. There is only the viewer who rejects the seduction, and instead projects upon the subject. Maripor saw elements of herself in Amadeo, and Amadeo exists now intertwined with her and her memory, which Molloy translated into Armand, who now himself is inextricable from this boy we know nothing about save that an artist once thought he was beautiful.

I won’t pretend to know why Daniel Molloy cast his dead wife, who by his own admission he never fell out of love with, as the Orwellian antagonist of his vampire erotica—it’s definitely not the most, um, flattering portrayal. But we’re also not seeing Armand/Alice at their best, yet. There’s obviously plenty of material for a sequel, given I just sat here and wrote all this based on a handful of paragraphs. If the core theme of Interview with the Vampire is “memory is a monster”, I’d love to see The Vampire Armand (or whatever he decides to name it) exploring the relationship between photograph and truth. Molloy has done some fantastic collaborative work with photojournalists in the past with Under the Burning Sky, and even if Armand didn’t use his skill with the Mind Gift to rewrite people’s memories (a well of untapped fictional photojournalistic potential), there’s this inescapable throughline with Amadeo/Armand/Alice and the rejection of photographic objectivity I’m itching to see explored.

Marlene Dumas argues that a photograph “takes”, where a painting “makes”. Marius de Romanus’ photorealism-before-photography depicts Amadeo with European coloring; Louis takes a blurry photo of Armand while trying to photograph his hallucination of Lestat, then later argues with a Parisian art dealer who believes he’s “caught the [fragile] soul [Armand] is hiding”; two years after Alice Maripor walks out on Daniel Molloy and is never seen again, Dumas paints Silence (1989) after the photograph of the two of them posted above, which was reproduced in a small memorial article in The Village Voice. That article didn’t say her death was AIDS-related (without a body, they couldn’t even say for sure she was dead), but that was the popular assumption—and considering Maripor had already linked the syphilis epidemic in Renaissance Venice to the HIV/AIDS crisis in her artwork, Daniel ascribing Amadeo’s death to “illness” feels as good as confirmation to me.

Dumas’ Silence (an allusion to the ACT-UP slogan “Silence = Death”), in depicting Molloy as a vague white outline like the chalk marking a corpse, turns the matter of life and death on its head. Maripor by contrast is lively, midway through a sentence—chatting away with the living dead. If a tree falls in the forest with no one around to hear it, does it make a sound? If an immigrant sex worker dies alone of a disease she probably couldn’t even be diagnosed with, does it make an impact?

Anyway, I don’t read minds, so I can’t say what Molloy’s going to do with Armand going forward. Maybe I’m reading into it too much and the curtains are just blue. (I am admittedly probably reading into it a little bit too much. Just a smidge.) But in Interview with the Vampire Daniel and Louis paint us a picture of a one-note pathological liar, and I don’t know what the truth is, but I know it isn’t that simple.

There’s this quote of Maripor’s (accompanied by a sketchy-looking monocolor lino print of Rachael from the movie Blade Runner) in an zine from 1984 called “MAKE A MESS!!” that I stumbled across in undergrad, and it’s stuck with me ever since. I invite you to read it now and remember that this is, apparently, the vampire Armand talking:

My arts education began with the old masters. I first learned to paint with egg tempera and oils—I do know how to paint “correctly”, I simply choose not to. But something about those mediums is, they’re very well suited to mistakes. You could work on the same panel for years and years if you wished, just scraping layers off and starting anew until it was perfect. With my art now, with the block printing technique, I suppose I’m trying to embrace imperfection. Because you’re cutting things away rather than building them up, everything you do wrong will make it into the final product. If your hand slips or you make the wrong incision, that’s that—there’s not really any fixing it, much as you might like to be able to. It’s like life, in a way. There is no absolution. What is broken will remain so. What is said cannot be unsaid; what’s done, never undone. I have a tendency to obsess over my mistakes, to… scrape away the paint and try again, over and over and over. Maybe this time, it will be perfect. With the lino, you have to give that up. It’s going to be full of all these mistakes, but you still end up with something beautiful, something worth loving. Or, I hope so, at least.

— A. MARIPOR

xunxar

xunxar

ELEVEN THOUSAND WORDS AND SOMEHOW I FORGOT TO TALK ABOUT GENDER

19,271 notes

graiai ContactOriginally published 28.11.2024 as part of Fic in a Box on the Archive of our Own. All artwork is original, created either by myself or unravelledclementines, all images were used with permission, all translations are my own, and all research is my own. The links within the "post" all go real places, but not necessarily where you think they do. Thank you for reading!

graiai ContactOriginally published 28.11.2024 as part of Fic in a Box on the Archive of our Own. All artwork is original, created either by myself or unravelledclementines, all images were used with permission, all translations are my own, and all research is my own. The links within the "post" all go real places, but not necessarily where you think they do. Thank you for reading!

Go back.